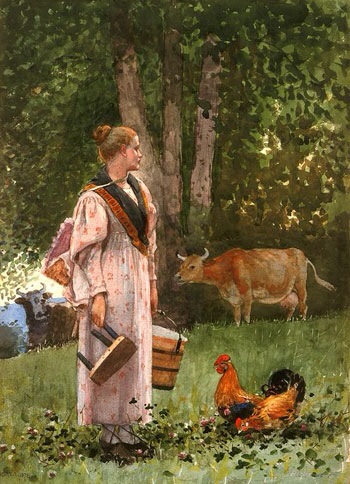

“‘I could not take my eyes from her face which grew larger as she approached, like a sun which it was somehow possible to stare at and which was coming nearer and nearer, letting itself be seen at close quarters, dazzling you with its blaze of red and gold.’ Proust wishes her to remain forever in his perceptual field and will alter his own location to bring that about: ‘to go with her to the stream, to the cow, to the train, to be always at her side.’” –Marcel Proust from “On Beauty and Being Just” by Elaine Scarry

Observers of beauty desire begotten immortality.

This is a fascinating assertion made by Elaine Scarry, Professor of Aesthetics at Harvard. Her definition of beauty is currently lost in translation in pop culture, which is why reviewing the points made, including those on replication and contractual agreements, primes the pump for a revitalized conversation on this well-worn topic.

Why does a man stare at a beautiful woman? According to Scarry, he stares because of his ardent desire to take in the beauty he sees until it becomes immortal, forever imprinted in his mind with all of its original, immutable features. Scarry says this: “The first flash of the bird incites the desire to duplicate not by translating the glimpsed image into a drawing or a poem or a photograph but simply by continuing to see her five seconds, twenty-five seconds, forty-five seconds later—as long as the bird is there to be beheld. People follow the paths of migrating birds, moving strangers, and lost manuscripts, trying to keep the thing sensorily present to them.”

You’ll have to forgive me for writing in essay form today, but it helps communicate her perspective, and I think her perspective is one that’s readily applicable to everyone from Facebook moms to LinkedIN execs.

According to the above quote, when we try to capture beauty, we recognize our mortal limitations, and observers of beauty desire begotten immortality. Once gone, the object of our admiration loses some of its original qualities in the fading recesses of our visual memories. How do we combat this in our quest to immortalize beautiful things? We find tangible ways to copy them. If beauty cannot remain immortalized in visual memory, we strive for the next best thing, to replicate it. “Beauty brings copies of itself into being. It makes us draw it, take photographs of it, or describe it to other people.” Beauty, upon becoming conscious of its tragic mortality, demands replication.

What’s the favored cultural choice for replication? The selfie. This self snapshot is a personalized way to copy our favorite moments, in freeze frame (recognizing their transience), with the hope that others will see and appreciate the aesthetic value. There’s an added benefit that others get to enjoy those moments with us. The selfie is a fun and practical way to mark events when others aren’t around to play the role of photographer, but as an example of beauty it falls short.

In selfies, the observed and observer are one and the same. The subject that is emanating beauty must attempt to copy itself. This may seem innocuous at first glance, but it deceptively supports the cultural ethos that tarnishes beauty’s reputation. This ethos is based upon a one-dimensional view of beauty that is superficial and self-conscious. Let me explain. In photography, the photographer plays the role of narrator, editing with the frame, choosing just the right light, and electing the exact moment to snap, the one that will best capture the edges of the human spirit. With the selfie the defined narrator is also the protagonist in the story. Therefore, the narrator loses essential perspective.

The outcome is this. What we end up capturing is not a self-forgetful photo that replicates beauty, but a contrived and self-conscious interpretation of what we think others want to see. In our self-consciousness we end up masking the attributes that would enhance others’ enjoyment of the aesthetic, we lose the three-dimensional replication. In this sense, the selfie is flat and one-dimensional. It captures us from the physical angles we believe enhance beauty–the eyes and cheekbones and lips, and these traits can be very appealing–but in our preoccupation with being photographer and subject, simultaneously, we lose our ability to unconsciously express a soulful beauty. The contrived nature of the photo whittles away some of the genuine expressiveness that would enhance the emanating internal beauty.

The exception to the selfie rule is when there’s more than one person in a selfie, at which point you may see less self-consciousness from those who aren’t playing the role of narrator. This advances the argument that beauty is best captured by an observer who is other-than the object of beauty itself.

Have you ever seen the candor in a captured expression that enriches the picture because of its self-forgetfulness? For example, a surprised or wide-eyed look, an unabashed and wide grin? These are all vestiges of the internal beauty rising to the surface at just the right moment of replication. Often, this effect is due to the interaction between the photographer and subject, an interaction that advances the storyline. This robust and non-superficial snap of beauty is best captured when the subject is acutely unaware of what he or she is emanating.

When we replicate beauty through photography, the interaction between photographer and subject can enhance the emergence of beauty in ways that allow it to be photogenically captured. This interaction hints at the communal nature of aesthetic emergence.

If beauty demands a separate observer (narrator) to interpret and replicate it, then beauty cannot be self-interpreted or solitary. “At the moment one comes into the presence of something beautiful, it greets you. It lifts away from the neutral background as though coming forward to welcome you—as though the object were designed to ‘fit’ your perception. In its etymology, ‘welcome’ means that one comes with the well-wishes or consent of the person or thing already standing on that ground. It is as though the welcoming thing has entered into, and consented to, your being in its midst. Your arrival seems contractual, not just something you want, but something the world you are now joining wants.”

The moral of the story? If we apply Scarry’s definition, then beauty is best interpreted, replicated, and celebrated not in the solitude of the selfie, but in engaged and receptive community.

I truly hope that you who are camera shy will reconsider allowing yourself to play the singular role of subject. I hope you will take the risk of being photographed at varied angles and with unfiltered expressions knowing that beauty may emerge in unexpected ways, and interpreted differently than you would interpret it yourself. Can you dare to allow your beauty to be interpreted by other narrators? Can you dare to believe your own attractive qualities, when replicated, may contribute to the well-being of your community?

Communal observers of beauty desire begotten immortality, because true beauty points to that which is life-giving.

Amy,

It’s so relieving to think of beauty as a communal flow; that others can benefit from our true expressions and that we can benefit from others true expressions. We would be passing along living beauty (to nourish each other’s souls), rather than contrived beauty (for others to admire but not get to really connect with). As I was reading, I was relating the soulful expression of beauty in a snapshot, to the soulful expression of beauty in daily living; how sometimes we express ourselves with masks on and sometimes we express our genuine selves. Can you help me understand more about how it affects the community when we free ourselves to express our genuine qualities? I remember you mentioning in a previous blog post that when we express who we are, it frees others to express who they are. Maybe, when we express ourselves without masks, we can see each other’s souls more, and that invites us to explore our humanity more through another person. If masks where present we would be robbing others of the chance to explore what it means to be human-I feel like you may have mentioned this idea also in previous blog post. So, I guess my conclusion is we could help others experience more of who they are through our unmasked expressions of ourselves. What do you think?

Marina

Marina,

I appreciate your willingness to explore these ideas. There is certainly an element of reflective identities when expressing ourselves to others. There’s also the foreshadowing of beauty and truth as intertwined–when we express beauty, truth will inevitably follow. This isn’t the prevailing opinion, but is part of how I define beauty. If beauty and truth are intertwined then we help others see truth as we reveal beauty and, conversely, we reflect beauty as we share truth.

Are selfies the new narcissism?

Hi Jim,

IMO, if the selfie is a means to advance a cause then it’s neutral. It’s the cause that is or isn’t narcissistic. Communal responses to selfies can reinforce and advance narcissism or suppress it. It would certainly be true that if we’re looking for validation and people respond to our selfies positively, we’ll continue and increase the behavior. If people respond negatively, on the other hand, we may decrease the behavior, but this won’t necessarily decrease the self-conscious response. Our internal hurt over being ignored can increase self-loathing. It can be a vehicle for narcissism, along with many other things. And we’re prone to feed off of that which makes us feel better, or be overcome by that which makes us feel worse, both leave us self-conscious. But there are many great uses for selfies, and many great stories that can be told through them. Wouldn’t want to throw the baby out with the bath water. I’d be curious to hear your answer to the question.